“Nothing is more effective at dropping feed intake than feeling sick.”

– Prof. Lance Baumguard at the 2019 Ruminant Gut Health Conference.

Defining the problem

Farmer: “Alex, I have a fertility problem. Can you help?”

Alex: “Sure, can you define the fertility problem?”

Farmer: “Not really, they just aren’t where I feel they should be.”

This is possibly the most common exchange that we, as the agricultural support industry, encounter. The client knows something is not right, but is unsure what it is, why it is, and what to do about it. Moreover, he sometimes has no idea whether it is a big issue that he must devote effort to, or just a small issue that he can let slide. He instinctively knows that his cows are not as healthy as they should be and that it is costing him money. Moving beyond gut feel and into the realm of defining the issue and setting goals to fix it is far more difficult.

Searching for solutions

Maximum profitability requires cows to be happy, healthy, and effective at turning their feed into milk. Much of this efficiency is directly affected by the health and comfort of the cows. In solving the fertility issue at hand, I always remind myself that the cause of an issue is seldom found in the same place as the issue, and the cost is almost always bigger than you think.

Let’s look at this fertility problem. As we sit chatting in the parlour, I notice that the cows in the herd are generally on the thin side, several are showing signs of lameness (but not limping yet, so they are not on the treatment list), and I discover that ketosis is something that they treat for a lot. The farmer asks if there is anything he can do for his milking cows to help them get into calf easier, can he change the diet, add minerals or buffers, etc.? He is looking to solve the issue where he sees the issue. Body condition score, hoof health, and ketosis are not ‘in the same place’ as fertility, but this may very well be where his easiest gains will be made towards the goal of profitable cows.

Defining the situation

Defining the current losses on a farm gives us a target at which to aim our efforts and will allow us to choose the best remedy. Thin cows experience a strong negative energy balance and partition energy from milk production to body reserves. They are also more likely to go lame. Whenever ketosis or milk fever is mentioned, the dry period should be our focus. So let’s try to put some data and figures to the situation.

Lame cows don’t walk and don’t eat properly. Thin cows lose the cushion of fat under their feet that helps absorb the impact of walking and this causes the pedal bone to drop and cause great discomfort in the foot. Moderately lame cows (cows that score 3 out of 5 on the lameness scale) lose 8% of their milk. They are also 2,8 times more likely to have increased days to first service, 15,6 times more likely to have more days open, 9 times more likely to have an increased number of services per conception, and are 8,4 times more likely to be culled.

Let’s get calculating

If the top group in the herd (50% of the herd on a seasonally calving dairy farm) is producing an average of 27 ℓ per cow per day, and half of that group is moderately lame as described above, then this implies a direct milk loss of R87 480 per month, excluding the cost of the negative effects on fertility.

Therefore, 27 ℓ x 8% = 2,16 ℓ per cow per day x 300 cows (half the top group is a quarter of the herd) = 648 ℓ/day x R4,50/ℓ = R2 916/day x 30 days in a month = R87 480/month lost.

Dr Dick Esselmont estimates that ketosis in the United Kingdom costs £0,0288/ℓ (R0,54/ℓ) in treatment costs and lost milk. Across the herd this equates to R338 265 for the first month of lactation! Based on a realistically high rate of 60% ketotic cows in the top group in the first month of lactation: 600 cows x 60% = 360 cows x 27 ℓ = 9 720 ℓ/day x R0,54 = R5 248,80 lost per day x 30 days = R157 464 lost on the first month of lactation.

In addition to these costs, every dairy farmer knows that cows that do not fall pregnant cost us money every day. In 2006, Albert de Vries estimated the cost per extra day open to be between $3,19 (R47,40) to $5,41 (R80,39) per cow per year. In KwaZulu-Natal, the number that is commonly used is R45 per day open, which means that, across the herd, the direct cost of an extra week open is: R378 000 (1 200 cows x 7 days x R45/cow = R378 000).

The cost of the solution

Taking all these calculations into account, we now total just over R600 000 in potential losses due to the so-called fertility issue. Many of these issues will be caused by an imbalanced and/or poorly managed dry period. If we decide to only spend half of this additional cost on a solution, we have approximately R300 000 available, or an additional R12 per cow per day to improve our 21-day steam-up period.

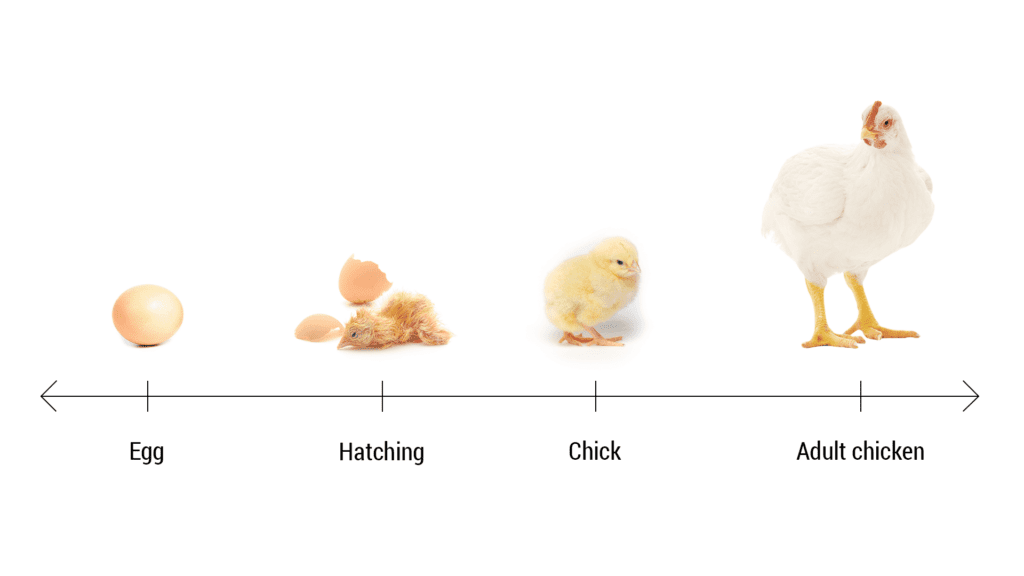

This means we can consider using a more expensive dry cow ration with balanced anionic salts. We can drastically improve the mineral nutrition and improve immunity and ease of transition. We can expand our colostrum-handling facilities and systems in order to improve the nutrition supplied to the next generation of calves.

Conclusion

Defining the issues we face and setting goals to solve them is the best way to understand how we are investing in our dairies. It ensures that we do our best to keep our cows healthy, happy, and profitable.

Calculations are based on a herd of 1 200 cows in milk, with the following assumptions: milk price R4,50/ℓ, R14,86 to the dollar, R18,87 to the pound, average milk production for the herd is 19 ℓ, average milk production for the top group is 27 ℓ.

References

- Zinpro First Step®: Dairy Lameness Assessment and Prevention Program.

- “The costs of ketosis – the hidden cash killer”, presented by Dr Dick Esslemont, a consultant in dairy farm management.

- De Vries, A., 2006. Determinants of the cost of days open in dairy cattle. Proceedings of the 11th International Symposium on Veterinary Epidemiology and Economics.

Alex Jenkins is a technical specialist in the ruminant team at Chemuniqué and holds a master's degree in animal science from the University of KwaZulu-Natal.