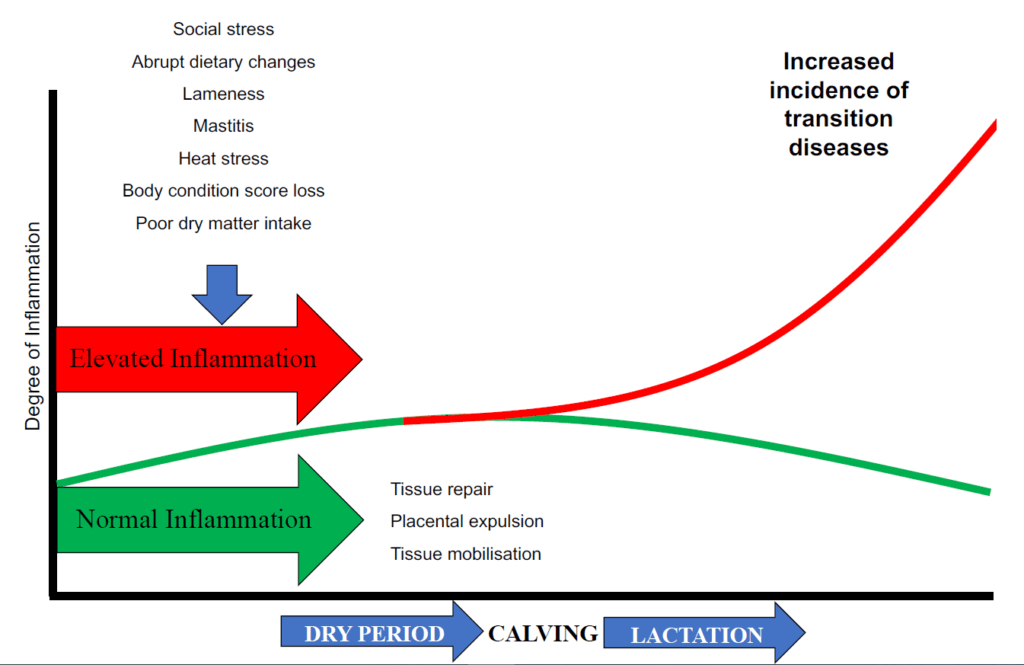

This article is the first in a series explaining how reducing the extent of inflammation, the hidden milk thief, in transition cows can be the key to reduced costs and increased production.

Inflammation

It’s a situation every dairy farmer has encountered. Fresh-calved cows just not milking as well as expected. The typical response is to assume cows are short of energy and to increase the amount of concentrates fed in an attempt to increase yields. The more cost-effective approach is to help them make better use of the energy they are already being fed, and the key to this is tackling the issue of uncontrolled inflammation, the hidden milk thief.

An essential mechanism

Inflammation is the body’s response to injury and its way of signalling the immune system to heal and repair tissues, as well as defend itself against foreign invaders, such as viruses and bacteria. It is a sign that the body is trying to heal itself. The clue is the magnitude and duration of the inflammation experienced by the cow.

Controlled inflammation is a normal part of transition as cows recover from parturition and re-adapt to milk production. But uncontrolled inflammation is associated with over-conditioning, excessive loss of body weight, infections such as mastitis, and damage associated with conditions like acidosis and lameness, and is the gateway to transition failures.

High energy expenditure

These processes demand high energy expenditure, crucially robbing the cow of the precious glucose needed for production and other essential bodily functions. Glucose is the principal energy driver for milk yield, but also plays a central role in the initiation of oestrus and getting cows back in calf.

Early in the lactation, anything that diverts glucose risks reducing production and compromising fertility. Once a challenge occurs, inflammation and immune responses are a higher priority for glucose, as the cow is biologically conditioned to look after herself first.

Any inflammation will see glucose being diverted. The worse the inflammation, the more production will be affected, and simply feeding more will not always resolve the problem in the short term. A cow requires 100 g of glucose to produce 1 kg of milk, but an extreme inflammatory response consumes 1 kg of glucose every 12 hours, leading to 10 kg of milk being lost over the same period, or 20 kg per day.

Low energy supply

Cows respond to low energy supply by increasing the mobilisation of body reserves and accelerating body condition loss. This actually makes the situation worse, because although fat cells release energy in the form of fat, the processing of the cells creates toxins, triggering inflammation and increasing glucose demand. Excessive body condition loss is associated with a greater immune response, diverting even more glucose from production and compromising liver function by causing fatty liver and ketosis.

Boosting glucose supply

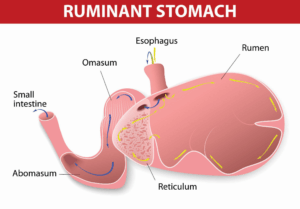

Common strategies for boosting the supply of glucose, when dry matter intake is compromised in early lactation, include increasing the energy density of the diet by feeding starch. However, using this strategy to compensate for energy lost due to inflammation can be counterproductive as it may cause an acidotic state. Acidosis in fresh cows can lead to inflammation, as well as a raft of other conditions.

Good management practices

Loss of milk production is only the tip of the iceberg when glucose supply is diverted to fight inflammation. Low glucose will reduce reproductive performance, increase the incidence of transition-related diseases, and ultimately result in increased culling. Good management can reduce the consequences of excessive inflammation and can be a more cost-effective solution to the problem than trying to increase glucose supply.

It is vital to maintain the integrity of the digestive system, as acidosis is a major cause of inflammation in the gut. Maximising dry matter intake during the transition period is essential. Ensure that there is adequate feed trough space to allow cows to eat when they want to without any risk of being bullied. Pay close attention to cubicle design and to how often cows are bedded down to encourage them to lie down more comfortably and help reduce lameness. Lameness can compromise dry matter intake, and is another source of inflammation that can add to glucose demands. Target no lame cows in the close-up group and hoof-trim all cows at drying off.

Another priority should be reducing stress. Minimise group changes as stress leads to an increase in cortisol levels, which in turn reduces dry matter intake and increases body condition loss with dire consequences for glucose supply. In the summer, it is especially important to do everything possible to mitigate the impact of heat stress on transition cows.

Concluding remarks

Uncontrolled inflammation and reduced dry matter intake in transition cows can be controlled by good management, resulting in higher yields, increased lifetime performance, and a more efficient transition. Lastly, the dietary intake of the trace minerals and vitamins that help the cows manage their immune response is sometimes overlooked during the transition period.

The higher demands for trace minerals and vitamins can actually be identified around calving, given the fact that the calf is demanding a final effort from the dam to deposit and differentiate tissues and organs. On top of this, the onset of lactation and recovery from pregnancy adds to the cows’ requirements. Correct supplementation, designed for transition, can yield hefty benefits for a minimum amount of investment.