Prevention cuts losses from painful claw lesions | |||

| Taking measures to prevent claw lesions in sows and gilts could save both you and your animals a lot of pain, according to a leading veterinarian in Germany.

“When a sow or gilt experiences lameness and pain due to a claw lesion, her reproductive potential is severely limited and she may need to be removed from the herd,” says Christoph K.W. Mülling, DVM, professor at the University of Leipzig. Today’s sows and gilts face a multi-pronged threat from claw lesions. The risk of the claw developing a painful and debilitating lesion is based on its interaction with the flooring surface, overcrowded conditions and aggressive social behavior. And lameness is expected to become an even bigger issue now that more animals are in group-housing environments. In Europe, some producers have reported seeing a higher incidence of claw damage and sow lameness since making the switch to group housing. “The sudden stops and turns associated with the increased social interaction found in group housing are causing serious claw injuries,” Mülling says. Despite the poor prognosis for a sow experiencing claw lesions and lameness, swine producers can help by adopting a routine claw-trimming program. Understanding lesions and lameness According to Mülling, one of the critical factors contributing to claw lesions in today’s swine operations is concrete flooring. The pig’s foot is anatomically designed for a soft, variable, uneven surface with two claws and two long dew claws to provide support. “When we place the pig on concrete, we are changing the mechanics of the foot and how it interacts with the flooring surface,” he says. “The result is lesions related to inflammation, mechanical injury, and horn and tissue quality.”

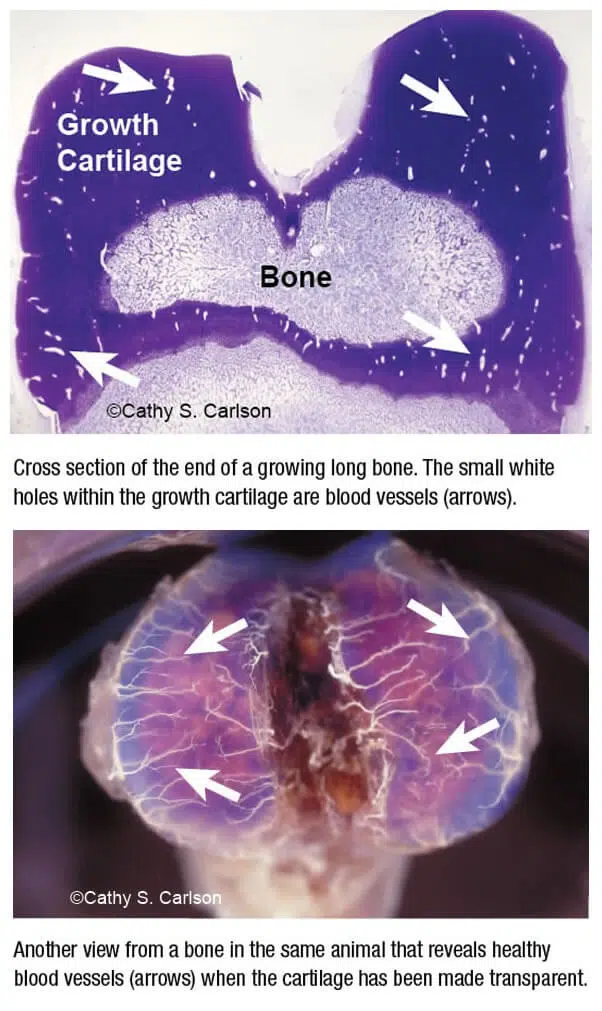

Histopathology — the microscopic examination of tissue — allows Mülling to understand the relationship between the cause, nature, stage and severity of claw lesions (Table 1). “Once we understand the origin of lesions and their sequence, we’re better able to develop preventive measures and improve management in our herds,” he says. “This knowledge helps us decrease the incidence of claw lesions and improve animal welfare.” A sow’s claw is composed of a very hard horn wall, very hard sole and very soft heel horn. The shock-absorbing mechanism at the rear is composed of the rubber-like elastic horn at the rear of the claw and works in conjunction with the shock-absorbing subcutaneous fat cushion. When sows fight, their quick, sharp movements create a shearing force within the claw. This results in a crushing action within the claw that effectively destroys tissue. “With a sudden stop or turn, the tip of the pedal bone moves into the tip of the claw capsule, an area without a shock-absorbing fat cushion,” Mülling explains. Concrete flooring also favors the development of long toes and overgrown heels. The long toe acts as a lever when the sow walks, increasing pain at the junction of the sole and heel horn. Overgrown heels also result from the mechanical interaction of the sow foot on concrete.

“Walking on smooth, flat concrete removes the dew claw from interaction with the floor while increasing the pressure on the toes,” Mülling explains. “This, in turn, causes excessive friction due to slipping on the heel, resulting in hyperkeratosis — an overgrown heel with an excessive build-up of skin — similar to a callus on your palm from using a shovel or garden fork.” The increased pressure by the overgrown heel puts more pressure on the living tissue, causing pain, he adds.

In today’s swine production systems, the long toe and overgrown heel are frequent trouble spots (Figure 1).

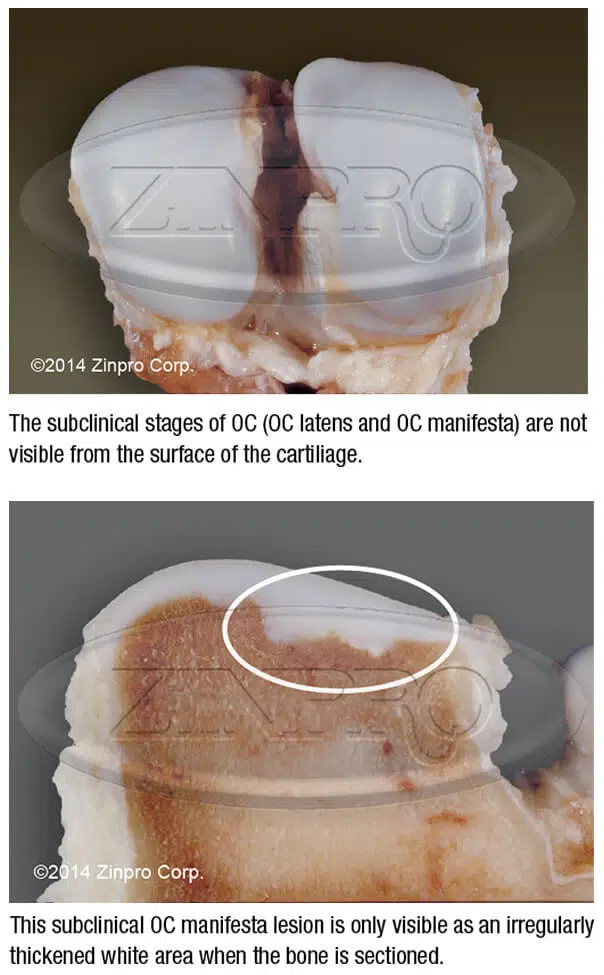

Another area at risk for developing cracks and lesions in the sow’s foot is the white line junction of the vertical claw wall and the sole. Pig claws show sudden changes in horn hardness, making them more vulnerable to separation and cracks at this white line and at the heel wall junction. The horn produced under these conditions is of inferior quality and more prone to developing cracks and tissue separations, which ultimately result in exposure of the dermis — and opens a path to infection. The white line is a weak spot for the foot with its hinge at the soft brittle horn (Figure 2). White line cracks not only involve separation of the dermis from the hoof wall, they also create an exposure site that allows bacteria to enter, leading to infection and inflammation, which increase pressure and pain inside the claw.

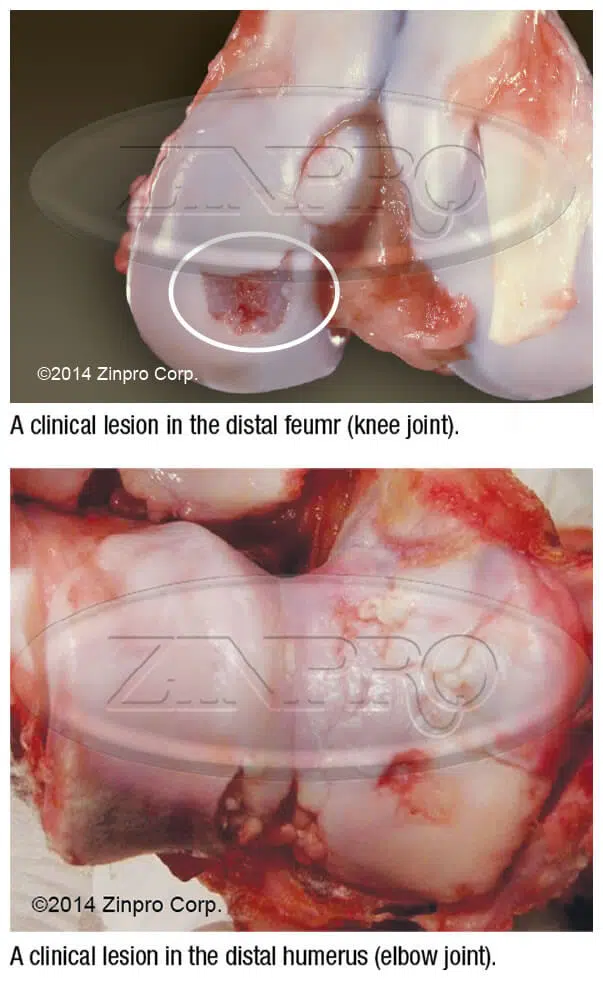

The zipper-like separation associated with the white line lesion is particularly dangerous and prone to infection. With only a couple of millimeters separating the surface of the white line and the underlying living tissue, an opening here exposes the dermis, resulting in secondary infection, inflammation of the dermis, tissue destruction and severe lameness. Alterations of the white line are more likely to cause lameness in sows than other lesions (Figure 3). “Without intervention, the exposure of the dermis, infection from bacteria, inflammation and its associated edema and swelling result in increased pressure within the confinement of the horn capsule, causing severe pain — similar to hitting your thumb with a hammer,” Mülling explains. Unfortunately, once the bacterial infection reaches the joint, regardless of the origin of the lesion, it is too late to return the sow claw to health and the sow to production. Preventing claw lesions Balance of the sow’s foot is a critical area to address in the prevention of lameness and claw lesions. For instance, simply trimming the long toe rebalances the foot and stops the proliferation of heel growth — and the pain associated with the overgrown heel. “Producers can realize gains in sow productivity by implementing a regular claw-trimming program,” he adds.

The development and maintenance of a strong claw is dependent on adequate nutrition. Proper trace mineral availability, including the feeding of zinc, copper and manganese as amino acid complexes (Availa®Sow), helps decrease parakeratosis, which is often associated with zinc deficiency and results in poor hoof quality through the incomplete formation of keratin; it also predisposes the claw to cracks and tissue separations. Hoof hardness also plays a critical role in maintaining the quality and structural integrity of the claw. While researchers continue to explore factors relating to hoof hardness, it is clear that genetics and nutritional deficiencies play critical roles. “Through research studies, genetic improvement and management techniques, swine producers have the opportunity to reduce, and even prevent, the painful claw lesions that decrease not only productivity of the sow but her welfare as well,” Mülling says. For more information: Contact your Zinpro Performance Minerals representative or click here.

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Feet First® Update is a publication produced by Zinpro Corporation and the Feet First Team, an international collaboration of researchers, veterinarians and nutritionists. The Feet First program focuses on swine welfare and helping improve the efficiency of pork production through the identification and prevention of lameness. Articles may be reprinted with prior permission. Performance Minerals® and Feet First® are trademarks of Zinpro Corporation. ©2013 Zinpro Corp. All rights reserved. You are receiving this email as a courtesy from Zinpro Corporation. Please know that you can unsubscribe at any time by sending us notice in writing, by calling or by clicking the unsubscribe link below. 10400 Viking Drive, Suite 240, Eden Prairie, MN 55344, USA • www.zinpro.com • +1 952-983-4000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

Chemuniqué empowers feed and food producers with the most innovative animal performance solutions, enabling our clients to consistently advance the efficiency of production.