Incidence, severity of sow lameness hinge on

flooring, pen design and animal aggression

As the European swine industry moves from individual stalls to group-housing systems, producers need to take extra measures to prevent foot, leg and muscle injuries that could become more prevalent with the sows’ increased movement and direct interaction with other animals.

|

Such injuries can lead to sow lameness, which can greatly increase culling rates and significantly decrease the breeding herd’s performance and profitability. Factors such as flooring surface, pen design and the producer’s ability to decrease aggression will help to minimize injuries and decrease lameness, says Herman M. Vermeer, scientific researcher and project leader, Wageningen UR Livestock Research, the Netherlands. While numerous factors are responsible for lameness in sows, interaction with the flooring in their environment is an important starting point for maintaining claw and joint health, he says. More than 20 years of research conducted in the Netherlands has found that every farm with sows has lesions that can potentially lead to lameness. |

Vermeer: “…every farm with sows has lesions that can potentially lead to lameness.” |

Flooring options in group housing

Sows prefer different flooring types for eating, lying and defecating. This preference can be accommodated in group housing through the combination of solid flooring, slatted flooring and mats. For instance, a study found that sows housed on slatted floors were twice as likely to develop lameness as sows housed on solid floors (Heinonen et al., 2006). Furthermore, the odds of a sow becoming severely lame were nearly four times greater.

One of the most critical components of flooring related to lameness is abrasiveness or the roughness of the flooring. A floor that is too rough causes excessive abrasion resulting in white line lesions and horn cracks, while a surface that is too smooth is slippery and allows long toe growth.

“We’ve learned through our research that plastic and tri-bar flooring is simply too smooth to allow for adequate abrasion and claw grip on the flooring surface; this results in long toe growth and increased lameness due to slipping,” Vermeer says. “It is very important gilts be reared from 25 kg (55 lb) on a floor with adequate abrasiveness to provide wear and prevent long toes.”

“It is very important gilts be reared from 25 kg (55 lb) on a floor with adequate abrasiveness to provide wear and prevent long toes.”Vermeer |

Vermeer also notes that whether it is solid or slatted flooring, concrete — if finished correctly — is generally the best choice. However, in retrofitted facilities, retaining broken or chipped slats will result in more claw and coronary-band injuries. The slot and slat dimensions must also meet the EU regulations of 20 mm (0.8 in) slot width and a slat width of 80 to 100 mm (3.2 to 3.9 in) for sows and gilts. Straw bedding used in group housing can provide cushioning for the claw, but it also has the potential to be slick with manure slurry. This wet surface creates lameness problems when sows in a pen begin mounting behavior as they return to estrus. A slippery floor also contributes to muscle and joint injuries. |

“Dry, non-slippery floors are essential in preventing injuries,” Vermeer stresses. For instance, providing a large pen — with dry, soft flooring — for mixing sows during the first day after lactation helps decrease injuries and lameness caused by aggression and fighting.

The use of mats in the resting area of group-housing systems is gaining popularity. Mats offer several advantages, including improved grip of the claw against the surface, decreased shoulder bursitis and less pressure when sows are lying. However, they also pose additional hygiene issues and often retain heat in warm environments.

Proper pen design helps decrease lamenessPen dimensions (size and shape) are another big concern when moving to group housing from individual stalls. A square pen shape allows plenty of open area for sows while preventing narrow alleys where sows can become trapped by pen mates. Sows need room to avoid each other and escape from acts of aggression. This helps protect the young — and most valuable — sows from lameness and injury. Vermeer explains that maintaining 3 to 3.5 meters (9.8 to 11.5 ft) is crucial between rows of free-access stalls. This spacing permits sows to pass easily and walk into stalls without turning sharply and risking lameness, while sustaining optimal performance. |

Sows need room to avoid each other and escape from acts of aggression. |

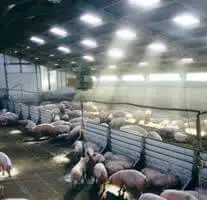

In terms of basic space needs, a sow requires 1 square meter (10.8 sq ft) to lie, and 1 square meter (10.8 sq ft) to move around, feed and defecate. EU regulations require 2.25 square meters (24.2 sq ft) per sow; however, in groups of more than 40 sows there is a 10 percent decrease in required space. Often in larger sow groups, the bigger pen size produces better individual results because there is more room for the sow to run away or hide in the face of aggression, he says.

Success in group housing

Limiting the factors contributing to aggression is key to successful group housing, Vermeer emphasizes. Ad libitum feeding, barriers to walk around, a portion of dry, solid, non-slippery floor and a localized defecating area are all factors that work to mitigate the effects of aggression between sows.

|

Large sow groups often produce better individual results due to the bigger overall pen size. |

Sows moving from individual crates to open pens lack social skills; therefore, a pecking order must be established within the group. While mixing of sows is inevitable, the best time is just after weaning in terms of safety for the feet and legs, Vermeer says. Even after the sows establish a social rank, mixing should be avoided during the gestation cycle to decrease aggression. However, once stable groups are established, remixing of sows back into their former group after the 3-week lactation period results in very little aggression because the sows remember each other. During the initial switch to group housing, sows see an increase in lameness during gestation and a decrease during lactation. “Sows in group housing can experience mounting behavior and aggression, which contribute to lameness,” Vermeer points out. “When they enter lactation they are individually housed on warm, dry floors and given plenty of rest which allows time for their injuries to heal.” |

However, after 2 decades of experience with group housing, he reports that swine producers in the Netherlands have decreased group-housing lameness problems to levels less than individual stalls.

According to Vermeer, when moving to a group-housing system, producers typically experience a drop in production for approximately a year. This drop is attributed to numerous factors including lack of socialization skills in older sows and learning a new management system for the swine producer.

“Learning proper management in a group-housing system takes time,” he points out, “but excellent results are achievable.”

Chemuniqué empowers feed and food producers with the most innovative animal performance solutions, enabling our clients to consistently advance the efficiency of production.