co-authored by Prof. L Prozesky

Ruminal parakeratosis refers to hardening of ruminal papillae and is associated with feeding a high-concentrate diet to ruminants. So what does the rumen tell us about parakeratosis? A low pH and increased volatile fatty acid (VFA) production in the rumen causes lesions that eventually cause the rumen papillae to keratinise (harden) and clump together.

Introduction

In ruminants, the forestomach consists of the rumen, reticulum and omasum. The internal surface (cutaneous mucous membrane) of the forestomach forms papillae, or folds, that are characteristic for each division. Rumen papillae vary in size and shape e.g. the mucosa of the reticulum has a honeycomb structure, while the omasum has broad longitudinal folds called leaves.

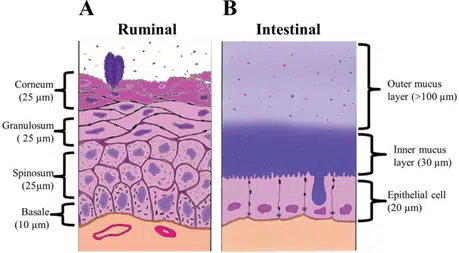

The ruminal stratified squamous epithelium is composed of four distinct layers with multiple functions (Figure 1). The stratum basale and stratum spinosum have functional mitochondria that contribute to the metabolic functions of the ruminal epithelium such as the production of ketones from short-chain fatty acids. The stratum granulosum is characterised by junctional complexes called desmosomes, acting as the permeability barrier of the ruminal epithelium.

What does the rumen tell us about parakeratosis?

When a ruminant is fed dietary grains, the production of VFA increases, and the rumen adapts by increasing the size of the papillae to maximise the surface area for fatty acid absorption. Under certain circumstances when the papillae increase in size, some papillae harden due to excessive epithelial proliferation with keratinisation – also known as parakeratosis. These papillae adhere together and form bundles that entrap food particles and bacteria (Figure 2). The abnormal epithelium and clusters of papillae decrease the efficiency of VFA absorption, causing poorer feed efficiencies.

It is speculated that causes of parakeratosis other than chronic acidosis include feed pelleting, a lack of roughage, and deficiencies of vitamin A and zinc.

Cure and prevention

Clinical signs of ruminal parakeratosis are often vague and difficult to pinpoint without a visual (macroscopical) confirmation of the lesions. Clinical signs include reduced feed intake, poor production, laminitis, liver abscesses, and diarrhoea. Clinically affected animals can be treated for acidosis to decrease the incidence of ruminal parakeratosis but the prognosis is poor.

Ruminal parakeratosis can rather be prevented by proper adaptation to concentrate rations, by proper feed bunk management (especially after rain or periods where animals stand without feed), the use of ionophores to decrease the number of lactic acid-producing bacteria, and provision of adequate fiber in the ration.

The key take-home message is to prevent ruminal acidosis. This will ensure that rumen papillae and microbes will stay healthy and effective and production will be optimised.

Anri Strauss is a scientific adviser in the ruminant team at Chemuniqué, holding a master’s degree in nutrition from the University of Pretoria. She grew up on a farm and still lives in the Free State, where she and her husband also farm with Boer goats.