Throughout history, mycotoxins have generally only been studied on grains, both stored and on-field, in order to determine their negative impact on both humans and livestock. These studies were undertaken mainly because grains are the main ingredient in both animal and human diets, with mycotoxins having the ability to remain chemically stable throughout food and feed processing. Over 400 different mycotoxins have been identified and classified according to their chemical structure and the symptoms they cause once ingested. Although studies on mycotoxins have focused on grains, pasture grazing by ruminants has revealed that mycotoxins are not only happy to grow on field grains and in storage, but on pastures too.

A very real threat

Mycotoxins can grow on a wide variety of different grasses, such as tall fescue, Bermuda grass, and ryegrass. These grasses have a symbiotic relationship with an endophyte fungus that protects the plant from insects and other pests, while the grass provides a place for the fungi to live and thrive. Mycotoxin presence on pastures was reported as early as 1970, originally in New Zealand. Since then, mycotoxins on pastures have also been detected in Australia, the United States (US), and South Africa. Each of these different types of grasses revealed a variety of mycotoxins as well as cooccurrence.

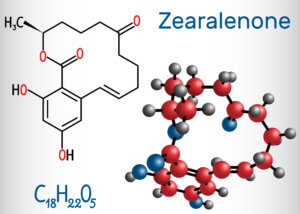

A study done on Bermuda grass in the state of Florida in the US revealed high levels of zearalenone present on some, but not all, grazing pastures. This proves again that mycotoxins will grow only in a specific environment that is suitable for their reproduction. Zearalenone is a mycotoxin that mimics the oestrogen hormone and is, therefore, able to interfere with normal reproductive processes in livestock, often leading to inability to reproduce, with abortions occurring in severe cases.

One study by a feed company in Australia revealed that perennial ryegrass staggers in sheep were being caused by the presence of ergot alkaloids. Once ingested, these mycotoxins cause an inflammatory response in sheep, resulting in higher rectal temperatures and respiration rates, decreased feed intake, and poor reproductive ability. These symptoms are, in part, the result of the activation of the animal’s immune system to fight mycotoxicosis. Besides the measurable symptoms, ryegrass staggers affect the animal’s nervous system, causing symptoms such as twitching and jerking, and the inability to move due to severe muscle contractions.

These studies prove that, although grazing livestock were generally considered to be at low risk for mycotoxin exposure, this might no longer be the case. Studies have revealed the presence of multiple mycotoxins, generally part of the trichothecenes family, as well as ergot alkaloids. Mycotoxins that occur in these groups include zearalenone, deoxynivalenol, ergovaline, and lolitrem B (one of many toxins produced by a fungus called Epichloë festucae var. lolii, which grows in perennial ryegrass), all of which are considered to cause severe mycotoxicosis in livestock with prolonged exposure.

Managing mycotoxins on pastures

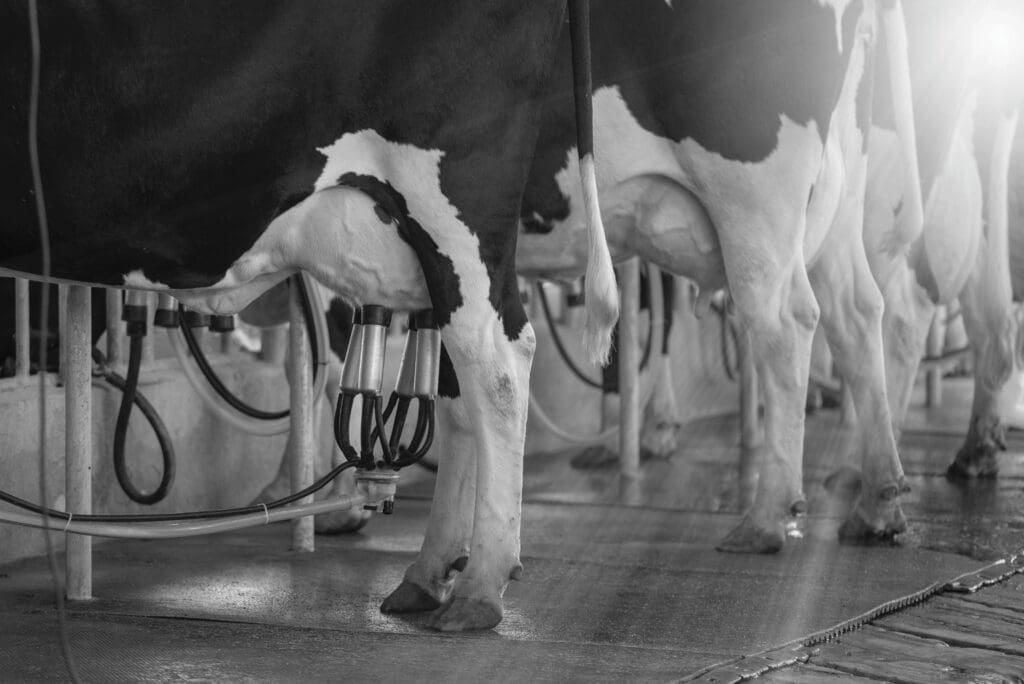

Constant monitoring is crucial when it comes to the complex diets consumed by ruminants. Both pasture grazing and silage consumption are vulnerable to attack by mycotoxins, especially in environments with a high moisture content and humidity. Although it is very difficult to detect mycotoxins on pastures without proper testing, animal health, reproductive ability, and overall production need to be carefully monitored, as they can be clear indicators of mycotoxicosis when related to the animals’ diets.

Introducing a mycotoxin binder can also help alleviate the problem. However, it should be emphasized that the mycotoxin binder used must be able to bind and wash out mycotoxins, as well as demonstrate decreased mycotoxin presence through mycotoxin deactivation and immunomodulation. This is necessary as little research has been done on the ability of most binders to treat mycotoxicosis caused by mycotoxins such as ergovaline and lolitrem B, which commonly occur on pastures. Good pasture management, constant monitoring, and prompt treatment are crucial to combat an enemy that is gaining ground in a world looking to maximise food and livestock production.

Heinrich Jansen van Vuuren holds a BSc in animal science from the University of Pretoria and is the team lead for amino acids, companion animals, and aquaculture at Chemuniqué.

An excellent article Heinrich. Deeply relevant to our pasture farmers whether feeding silage or just grass.