Microbes. The most populous of all life forms – trillions of them everywhere. There are highly specific populations on our hands, distinct from those in our mouths, or even on our forearms. Microbes occur on plants, in soil, on our buildings, and all over our farms and animals. Most are friendly and do no harm to us or our animals, but some microbes, like the nasty Gram-negatives, live on the dark side and cause disease and discomfort wherever they are encountered. In developing immunity, it is important to keep microbes in their place.

The ubiquity of microbes means that we are constantly in contact with them. While they are fine outside our bodies, once they get in, the story can change quite quickly. There’s a memorable saying, “Good fences make good neighbours”, and this is especially true of our relationships with these tiny organisms, especially when we are developing immunity. Constructing ‘good fences’ between us and our microbes has necessitated the development of some incredibly intricate defenses, and when these defenses fail, especially when they fail for our young animals, the results can be rapid and deadly.

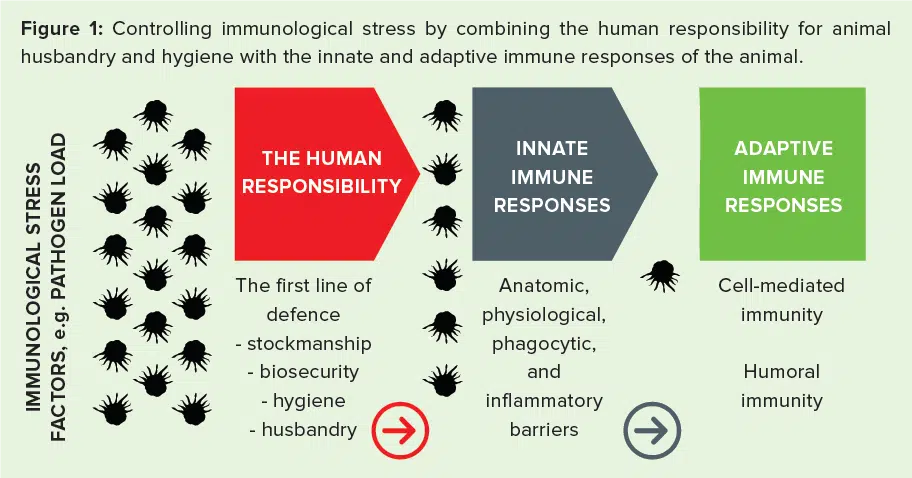

Three levels of protection

These defenses can be broadly broken down into three stages and the decisions we make during each stage will either help or harm the young stock that we will rely on in future years.

The first stage starts with you

While I am sorry to lay this responsibility squarely on your shoulders, I must ask you this: Have you ever asked your kids to wash their hands before dinner, or given them a bath? We do these things because we know that the number of microbes in an environment (the pathogen load) directly influences the chances of getting sick. While the calf is still developing immunity, stockmanship, biosecurity, and hygiene are all well within your control. They may take time, effort, and management, but they are the cheapest way to solve many of your problems.

Next comes your calf

She also has tiered defenses against invaders, the first of which is the layer of epidermis cells that protect her. Cells in her lungs and intestine are held together by tight junctions, a sort of protein upholstery job that locks cells together and keeps the barrier strong. These proteins are reliant on zinc to function optimally, and there is a direct correlation between leaky gut (where the tight junctions fail and admit microbes) and zinc levels in the animal.

Should any microbes get past the gut wall, the calf mounts her second defense, her immune system. White blood cells surf to the area on a tidal wave of increased blood circulation (the inflammatory response). Once they arrive, they attack and engulf foreign particles (the phagocytic response). More microbes need more white blood cells, the immune and phagocytic response needs fuel, and this comes in the form of energy from high-quality feed and minerals that are warehoused in the liver.

Lastly, the calf’s antibodies

The special ops forces that are trained to recognise specific enemies and target them with pinpoint accuracy are the most effective. Found both within and between the cells of the body, antibodies help the calf learn how to deal with the specific pathogens found on your farm. As we all know, a calf is born without antibodies and most diseases take hold in the first two weeks of life. So how do we mount an effective defense while the soldiers are still in training, while the calf is still developing immunity? We first build strong fences from the inside, and then we import soldiers from outside.

This is why colostrum management is so critical. Antibodies from the mother will protect the calf while she develops her own set of antibodies. Investing in optimal dry cow nutrition ensures that the best quality colostrum is produced; and after that it’s up to you. Get creative and find a way of getting two litres of high-quality colostrum into your calves within an hour of birth. Can you define ‘good-quality colostrum’?

Alex Jenkins is a technical specialist in the ruminant team at Chemuniqué and holds a master's degree in animal science from the University of KwaZulu-Natal.